Myanmar’s Pre-eminent Family of Dissidents with Progressive Politics

Biographers of Lenin have generally recognized the profound impact on Lenin of the radical politics of his older brother who was executed by the Tsar Nicholas II.

Well, multiply such defining experience in life of a dissident by five, and see how such profound experience would shape a person’s life, world view, and choices.

Read in Burmese: https://www.mizzimaburmese.com/article/131693

Imagine your father, a well-known writer and journalist, was imprisoned five times by various states in Burma, including the World War II-era colonial British, the post-colonial parliamentary democracy government and the post-1962 coup military dictatorship of General Ne Win, for doing what he considered “the right thing”, that is, using his pen to shed light on the political repression, racial and class exploitation and abuses of state power. Your mother – also a well-known writer – survived the British colonial police’s bloody crackdown of anti-imperialist student protests and processions in colonial Burma of the 1930s.

Your oldest brother, a card-carrying revolutionary, was executed in the late 1960’s by his own party – the Communist Party of Burma – in the Burmese equivalent of Mao’s Cultural Revolution when you were a teenager.

Your middle brother was locked up in solitary confinement in the prison in your native town of Mandalay for two years, subsequently shipped to the penal colony off the country’s southern coast for a total of six years, and freed only after the dictator General Ne Win decided to intervene and ordered his release.

And your mother, your father and you were hauled into military intelligence’s Kafkaesque detention in 1970’s for helping a fellow progressive on the run to successfully evade the dictatorship’s man hunt and finally escape across the borders into Southern China.

Subsequent to your first taste of the military’s jails, you yourself were imprisoned for 10 years in two different jails in 1990, for corresponding with your middle brother who escaped the military’s raid at home and ended up in exile in Southern China, while your wife was consequently left to look after three young children. And finally, you died in hiding, in poor health and with no easy or safe access to medical treatment, as the new military dictatorship was rounding up most of your fellow pro-democracy activists who supported the country’s flagship ruling party – National League for Democracy – in the aftermath of the 2021 military coup.

That’s, in a nutshell, a story of my fellow dissident Ko Nyein Chan who died at the age of 71 amidst the military junta’s escalating violence against civilian communities suspected of supporting democratic armed resistance throughout the country.

Ko Nyein Chan, died of natural causes at the age of 71 on 21 June 2023.

Nyein Chan (aka Nyi Pu Lay), the Person

Nyi Pu Lay (aka Nyein Chan), the nationally acclaimed writer and much-loved dissident from my old Dry Zone (or A-nya) town of Mandalay died of natural illness on 21 June 2023. Nyi Pu Lay’s life and revolutionary politics cannot be fully understood or appreciated without a proper glance at his extraordinary family.

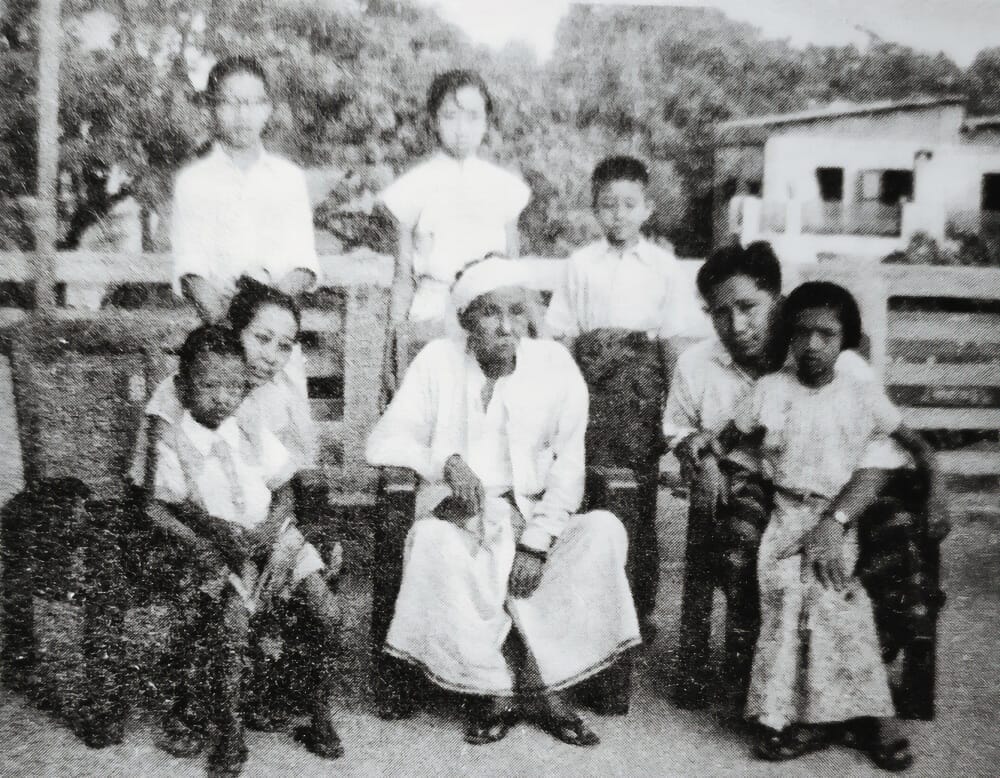

Nyi Pu Lay was the youngest child of five, in the family of nationally acclaimed writer/journalist parents U Hla and Daw Ahmar. There were three boys and two girls in the family, and all the boys including Nyi Pu Lay embraced the parents’ progressive values and principled opposition to exploitation and repression. The parents were extraordinary dissidents who were prepared never to bend to the will of abusive state powers, be the regime run by the alien colonizers or the “old nationalist friends” from the anti-colonial movement, or the tyrannical Burmese military leaders.

Ludu U Hla and Daw Ahma, their five children and Thakhin Kodaw Hmaing, the Iconic Cultural Leader of Burma throughout the anti-imperialist movement. (Nyi Pu Lay, front row, held by his mother, Circa. Mid-1950s.)

Several years younger than my own parents whose generation produced Captain Ohn Kyaw Myint, the 1976 ringleader of the abortive coup against Dictator Ne Win, Nyi Pu Lay’s oldest brother, named Ko Soe Win (born in 1941), studied at Rangoon University in the early 1960’s. After the coup of 1962, joined the armed resistance waged since March 1948 by the Burmese Communist Party or BCP. To the shock and disbelief of the Communist-inspired family, the BCP executed Ko Soe Win in one of their strongholds in Pegu Range, Lower Burma, in the heat of the internal purges, which mirrored Mao’s Cultural Revolution.

The middle brother Ko Chit Khin (popularly known as Hpoe Than or Hpoe Than Chaung or Mr Steel Rod for his steely toughness even during long periods of solitary confinement) was given severest punishment – shipped to remote Coco Island, established after independence, as a penal colony for ethnic self-determination fighters and communists. Anti-coup communist student leaders at Mandalay University, Hpoe Than Chaung and my own uncle the late Maung Cho were locked up by the coup regime led by General Ne Win in the early 1960’s. They belonged to two different factions of the Burmese Communist Party, Red and White flags. But they found themselves immediately adjacent to each other in two different cells. While my own uncle turned his back on politics and devoted himself to become a teacher until his retirement (and death) Nyi Pu Lay’s middle brother stayed his revolutionary course, using his powerful pen to agitate against the military dictatorship.

The middle two standing (from left to right) Ko Chit Khin (Hpoe Than Gyaung) and Nyein Chan (Nyi Pu Lay), flanked the two sisters, with their parents U Hla and Daw Ahma. Photo: circa. early 1970s (after Hpoe Than Gyaung’s release from 6-years imprisonment in Oct. 1972)

In October 1946, over internecine fights and distrust, Aung San as head of the post-World War II nationalist movement expelled the Burmese Communist Party from the WWII-era Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League, the umbrella united front against Japan’s Fascist occupation of which BCP was a founding member. Within 90 days following independence from Britain, the BCP declared armed resistance against the Parliamentary Democracy government of U Nu. The communists accused their old anti-imperialist comrades who now were in charge of the reigns of the newly independent Burmese government as “lackeys of the old colonizers” (or tools of the “neo-colonialists”). For Nu government consented to the protection of Britain’s commercial interests including the Burma Oil Corporation, Steel Brothers Timber Corporation and other extractive industries including mining interests. Nu’s government in return declared the Burmese Communist Party “illegal” and threatened to imprison the BCP leaders and the rank and file.

The parents established a publishing house – Prosperity and Progress or Kyi Pwa Yay in Mandalay and ran the newspaper – The People or Ludu – with a strong leftist editorial stance exposing injustices against the labouring classes, government corruption or political repression of dissidents.

They adopted as prefix to their names the name of their unapologetically progressive or left-wing newspaper Ludu or the People’s, and popularly known as Ludu U Hla or Daw Ahma. They were disdainful of the Soviet Union for flirting with the international capital, and looked, with admiration, to Maoist China as the truly anti-imperialist country, during the days of the Bandung Conference of 1950’s and beyond.

Both U Hla and Daw Ahma were nationally acclaimed, award-winning writers recognized during the civilian government of Prime Minister U Nu, their contemporaries during the anti-imperialist struggle against the British rule.

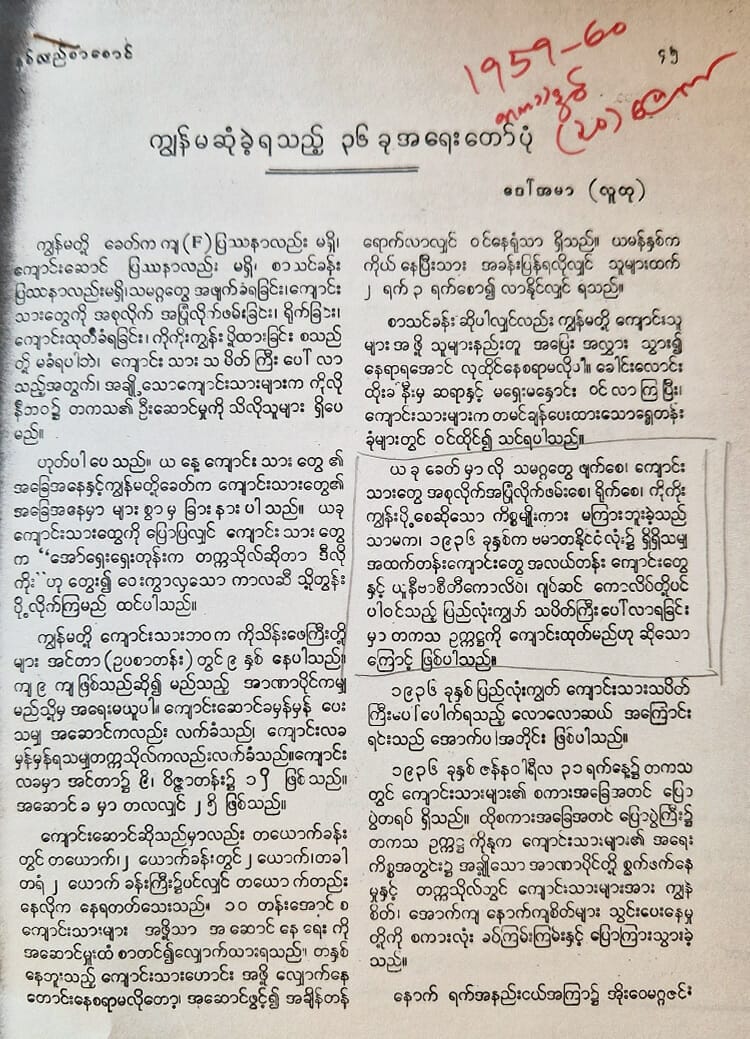

In their early 20s, both parents cut their anti-imperialist teeth in colonial Burma’s pre-war movements in the early 1930s against the British rule, which was fast-evolving from the western-educated elite-driven “Gentleman’s push for Home Rule with the Dominion status in the Empire ” of the 1910s and 1920s to the radicalized liberation struggle involving “direct action” on the streets, mass-mobilization and dissemination of Marxist-Leninist revolutionary ideas targeting the labouring classes of farmers and workers. The following is the photographic copy of Daw Ahma’s published essay in the 30th anniversary special issue of Oway (or Peakcock), to mark the founding of the Rangoon University Student Union wherein she railed against the post-colonial, Burmese nationalist government of U Nu (and from 1958-1960, the Caretaker Government of General Ne Win) for meting out severe punitive measures against progressive student activists from Rangoon University, her colonial alma mater.

The father U Hla hailed from Lower Burma and made his name as a writer and journalist in Rangoon, then the colonial capital, where the mother was involved as an anti-imperialist agitator through Rangoon University Student Union. His mother, Daw Ahmar, was involved in what she called “the embryonic revolution” of Student Strikes of 1936 – led by Rangoon University Student Union leaders the likes of whom were MA Rashid, Aung San and U Nu – which was followed by the nationwide multi-class “Year 1300 Revolution” (against the British rule) 2 years later in 1938 and 1939. (The Burmese year can be calculated by subtracting 638 from the Christian Era year).

His father U Hla came up for the first time to Mandalay, the centre of Upper Burma, as the representative of the writers’ guild in Rangoon, in February 1939 to deliver a brief address denouncing the British colonial authorities at the funeral of the 17 massacred anti-British Burmese protesters, who were instantly martyred by the rage-soaked city’s people.

Importantly, in the ensuing decades since the country’s independence, Nyi Pu Lay’s family milieu, with all the trappings of a bourgeoisie family – international travels, automobiles, comfortable life, intellectual and cultural pursuits – became the centre of progressive intellectual and scholarly life in Upper Burma, not just the city of Mandalay where his mother had deep root since its founding in the mid-19th century.

As the leading writers and journalists who were also entrepreneurially successfully as publishers, Nyi Pu Lay’s parents were in effect using their home and workplaces as the incubators for younger generation intellectuals, scholars, researchers, artists and writers who embraced the progressive perspectives – from art to literature, from religions to inter-ethnic relations, from state-society interactions. Nyi Pu Lay himself adopted a literary style best known as “Upper Burma Literary Movement”, which aimed to make the written Burmese easily accessible to men and women on the street vis-à-vis elitist formal style of Burmese literature which necessarily required former and higher learning.

His masterpiece “A Honey Drop On the Razor Sharp Blade” is a testament to the influence of his intellectual parents both of whom were among the pioneers of this “Literature for the People” movement birthed in Upper Burma.

Some of the country’s towering scholars, poets and writers made Ludu and Kyi Pwa Yay Press their intellectual hubs. Notable among them were Shwe Oo Daung (U Thein), the NLD Co-founder and journalist the late U Win Tin, former political prisoner and journalist the late Ludu Sein Win, the eminent Burmese historian, Dr Than Tun (deceased), the country’s best known painter the late Paw Oo Thet, famed poets (Communist) Maung Kyi Aung and Tin Moe – both deceased – the movie director Win Pe and the poet and librarian Swan Yi, now exiled in USA and the late movie actor and publisher Win Oo.

It is not hard to imagine the kind of sustained exposure that Nyi Pu Lay must have had to the extremely diverse “nutritious conversations, debates and discussions, having grown up in this type of intellectual and scholarly milieu.

His mother recorded many moments of anguish, mental torture and pains she and her husband endured during the 6-long years of their middle son’s imprisonment in Mandalay, Rangoon and Coco Island penal colony. Though heavily influenced by Communism and committed to the principles of freedom, justice and fairness, the parents did not turn their back on Buddhism, the cultural backbone of the dominant Burmese society at large, one would notice from the essays and letters, which were published in 2013, after her passing.

Admirably, the mother turned to both the Buddhist philosophy of Impermanence and her commitment to social justice-focused revolutionary ideals in coping with the deep pains of a mother whose husband and 3 sons had been subjected to the repressive state apparatuses. The personal/familial pains were the price her revolutionary family had to pay in trying to advance the unfulfilled goals of a just society free from various regimes which used the colonial state and its law, even in the post-independent period.

In front of their home in Let Hse Khan neighbourhood, she was seen making steamed rice and other offerings to the monks in her neighbourhood who were making their early morning rounds, collecting alms for their sole mid-day meals.

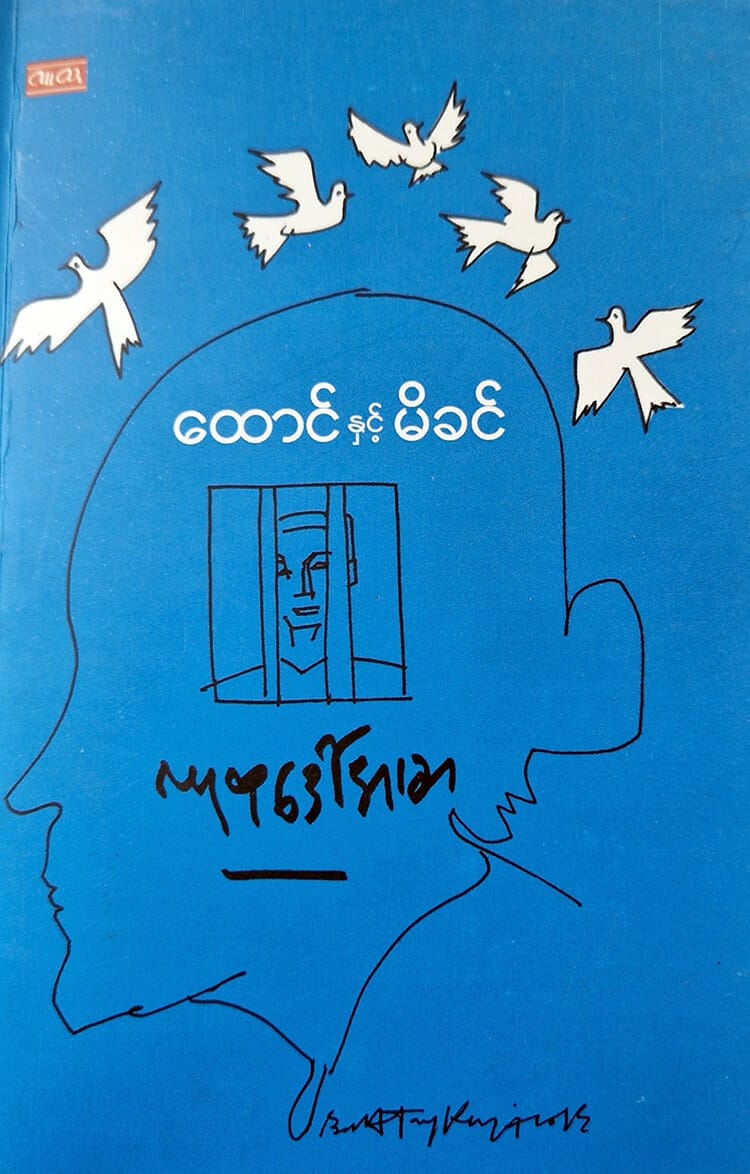

In the collection of very moving essays and letters (138-pages) to her jailed son which his mother started writing since his middle brother Hpoe Than Chaung (Ludu), barely 19, was hauled away from home by Ne Win’s military intelligence services (the dreaded “MIS”), a few years after the coup in 1962 – they were published by their family press Ludu or People, on the 40th anniversary of Hpoe Than’s release from 6 years imprisonment in 1972.

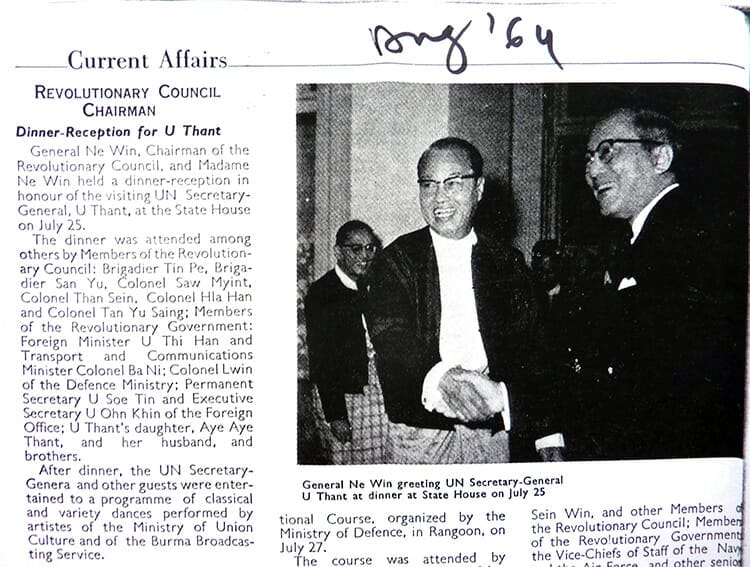

It is noteworthy that the Ludu family were actively resisting the Revolutionary Council, the coup regime led by General Ne Win, at a time some of the most prominent Burmese, for instance, the UN Secretary General U Thant, weres all smiles with the coup leader who ordered the indiscriminate killing of the estimated 300 Rangoon University students, all unarmed and peaceful, on campus.

Source: Forward Magazine, the official monthly mouthpiece of the Revolutionary Council, August 1964 issue.

The collection (see the front and back cover pictures below) was entitled “Prison and Mother”, published in 2013 with the brief but moving introduction by his middle brother Hpoe Than who talked of his late mother as just one of “many thousands of mothers whose children had been locked up” during half-century of Myanmar’s murderous military regimes.

In one of the moving personal essays his mother recorded making serious efforts to bring his 3-young children for prison visits to Tha Yet Prison, 350 miles away from their home city of Mandalay, by car and then by boat. She painfully articulated her reason for taking his children with her on family prison visits: that his middle brother Hpoe Than did not recognize either Nyi Pu Lay or his younger sister, upon release from 6 years behind bars – because they were unable to visit him on Coco Island penal colony in the Andaman Sea, and that she wanted to make sure that her youngest son would recognize his own children even after 10 years behind bars!

There I noticed how Nyi Pu Lay’s mother shifted her hope – from the executed son to the China-exiled Hpoe Than to her youngest to carry on running the family’s business of publishing and disseminating progressive literary works.

This was the wish which Nyi Pu Lay certainly fulfilled until he had to go into hiding with the violent coup of February 2021.

During the 1990’s at the height of the flagship National League for Democracy’s opposition to the military dictatorship known as the State Peace and Development Council Nyi Pu Lay’s mother publicly aired her political observation, which became a guiding revolutionary principle: “dictators never quit alive.” Conversely, she might as well have said, “neither do the revolutionaries.”

Nyi Pu Lay – might have lived longer had the circumstances afforded him better and easier access to medicine and treatment. Alas, Ko Nyein Chan, having been in hiding since the coup of 1 February 2021, he wisely chose his security and freedom over his needs for medical care, something he would not have had, had he been captured and jailed anyway.

The 7-decades of Nyi Pu Lay’s life – and those of his parents and 2 brothers – embody this indomitable spirit, which set the bar for anyone of us, Burmese or otherwise, who claim to wish to bring down tyrannical and murderous regimes.

Some people lead by their deeds, not their words.

The Nyi Pu Lay I knew

I had “known” him since he was in his early 20s – when I was barely a teenager – in the mid-1970’s during General Ne Win’s one-party military dictatorship.

We both went to the same grade school (K-10) (the well-known Catholic boys school St Peter’s which became State High School Number 9, after all private and missionary educational establishments were nationalized by General Ne Win’s Revolutionary Council, the coup junta). We both played table tennis and football in school albeit in two different generations.

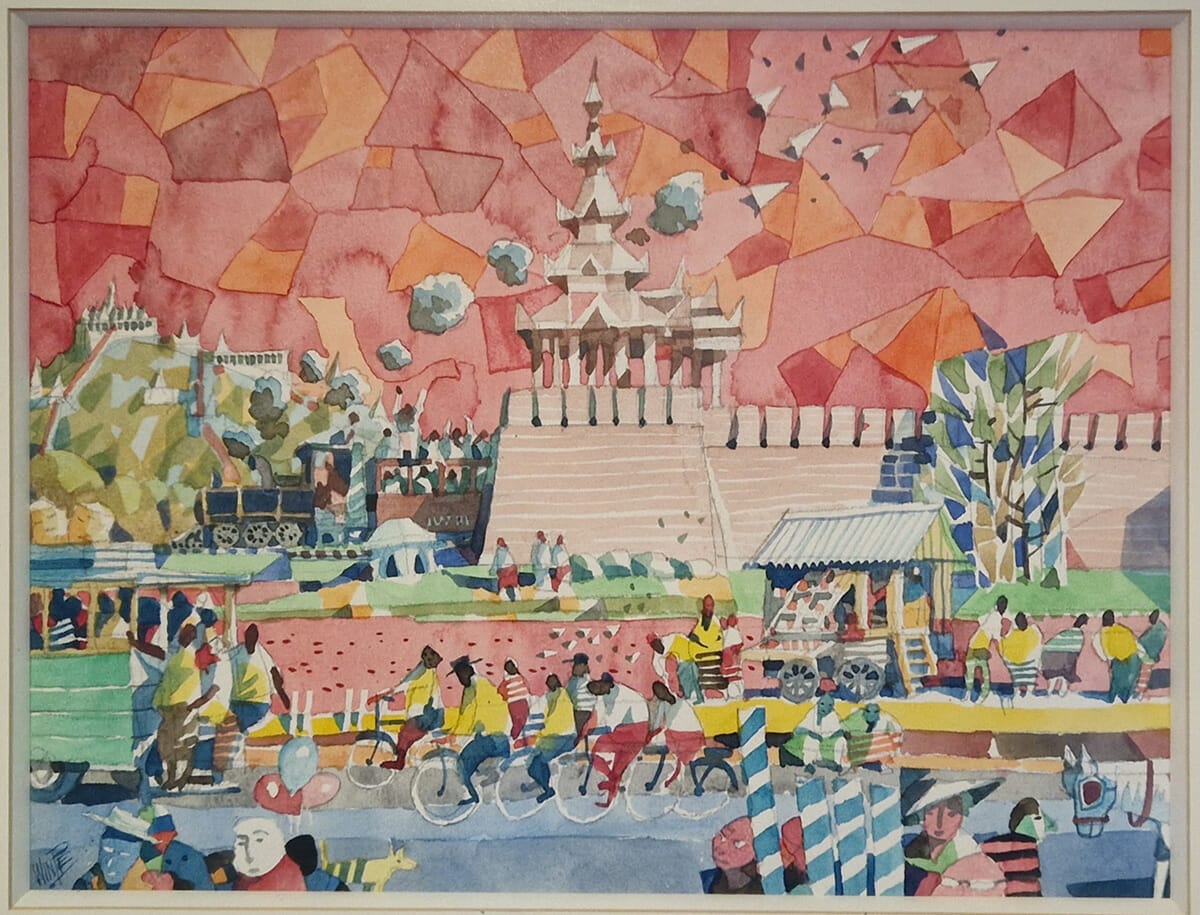

Nyi Pu Lay’s Mandalay, with its iconic Palace Wall, moat, and Mandalay Hill, Artist: movie director & former principal of Mandalay School of Fine Arts, (Mr) Win Pe, Washington, DC 1993

Nearly half-century later, I still recall the first time he came to play table tennis with one of my seniors at our club near Ba Htoo Stadium, a few minutes’ walk from my great-aunt’s house on the 30th Street in the Southern part of Mandalay where I was living as a middle schooler. He had then already matriculated from the same high school, after having repeated the high school final year several times, he was already attending Mandalay University, as a geology major. In the driveway in front of our table tennis club, a green VW bug, his parents’ car, was parked.

As a brief detour, in our city bicycles and rickshaws outnumbered private automobiles. During the military rule, our country was cut off from the outside world, and there were no new cars, or simply there were not many cars.

We remember which specific cars belonged to which families. Yes, in the old Mandalay with deep root in feudalism (the bygone Court of Ava) we spoke in the language of “families”, that is, the old, established families of the last seat of the Burmese feudal power.

As I stepped inside a small one-story building – which housed the Malaria and Leprosy Medicine Department of the Ministry of Health – where we played after office hours, I saw a skinny, brown-skinned player, a new face at the club, playing against Ko Tin Tun Aung, an early table tennis mentor of mine from SHS 9, several years senior to me in the same high school.

I was just a middle schooler, receiving some table tennis coaching at the club, just another kid who watched our senior players from the sidelines. A few years later I learned that he was preliminarily selected to be on the team representing Mandalay Division (or province) preparing to play in the national tournament. (In the 1960s and 1970s, Burma still had one of Asia’s top football teams, on per with S. Korea, Iran and Japan). I was excited to see him play football in Ba Htoo Stadium, which was literally 500 yards away from my house.

Looking back, I realize Ko Nyein Chan was what one would call a polymath, a man with multiple notable talents.

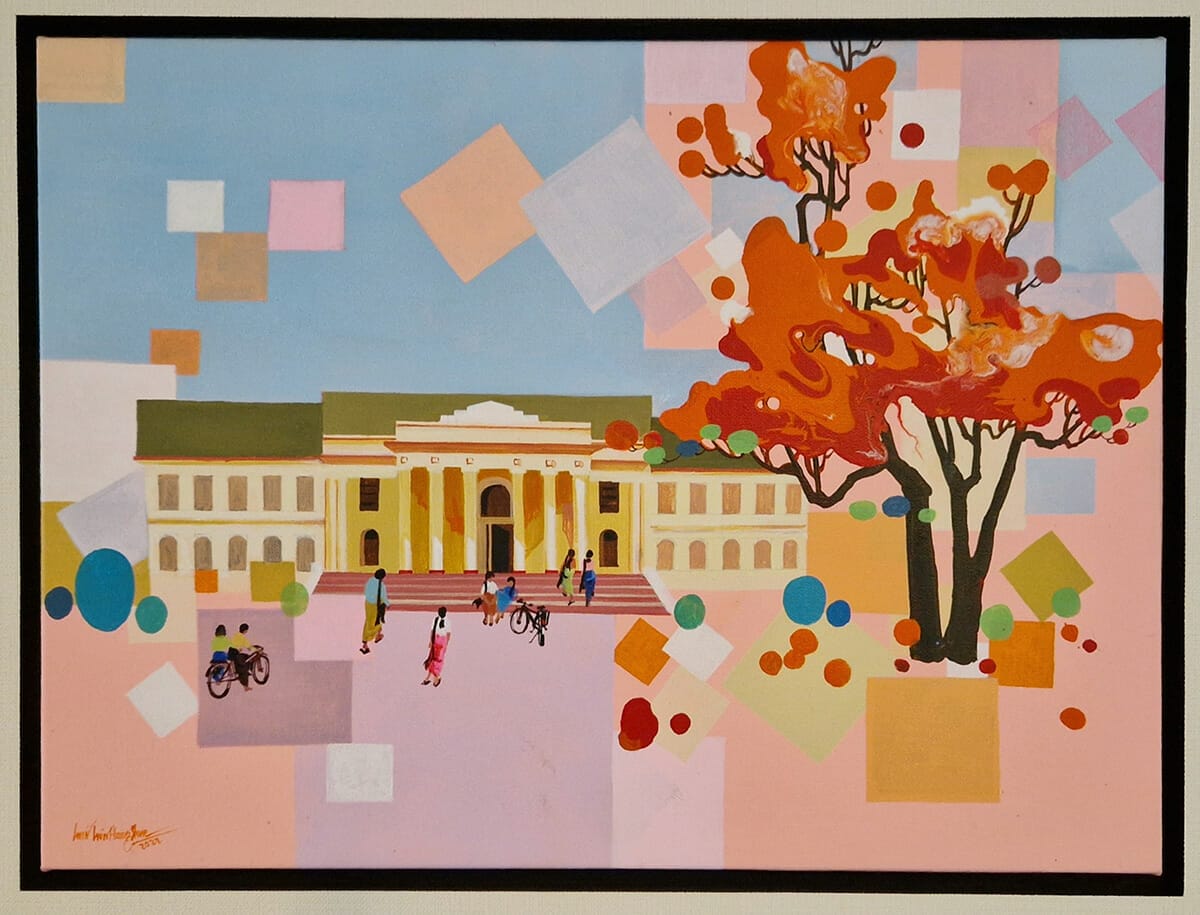

Nyi Pu Lay’s alma mater where he specialised in geology as an undergraduate, Mandalay University, with the iconic “main building”, founded in 1920. Artist: (Ms) Win Win Hlaing Shwe, Mandalay School of Fine Arts, 2022. (The author’s collection).

He tried his hand at painting, followed the footsteps of his parents as a writer and was awarded the prestigious National Literature Award by the transitional government of Aung San Suu Kyi in 2016. He played football for Mandalay University team which won the second prize in the nationwide inter-varsity tournament in the 1970’s when he was a member of the squad. [His father was a professional player with Rangoon Municipal Team in the pre-World War II years of early 1930’s.] An accomplished public speaker who criss-crossed the strife-torn and oppressed multi-ethnic country and used his writer’s voice to spread the ideas of progressivism, multiculturalism and anti-racism while nurturing the younger generation writers and dissidents after his release from prison some 20 years ago. He also took up “street photography” and published a collection of his photographic work, spanning across a few continents. Whenever the mood struck, he performed impromptu street theatre.

But I actually met him in person only in the context of our shared opposition to Islamophobia and, more specifically, the military-organized genocidal campaign against the Rohingya in Western Myanmar.

After the two bouts of organized violence against Rohingya in Rakhine state in June and October of 2012, I developed a crash course in racism, genocide and international law for educating Myanmar’s opinion-makers – “influencers” in today’s parlance of social media. With the help of the Genocide Documentation Center in Cambodia, a crucial pillar of the Khmer Rouge Tribunal, the Muslim-run Peace and Conflict Studies Center in Bangkok and the International Network of Engaged Buddhists, also in Bangkok, I would bring a few dozen Burmese artists, writers, teachers, grassroots organizers and religious leaders, including Buddhist monks and nuns and Christian and Muslim clergymen to Cambodia and Thailand for an intensive educational program.

In one of these batches, I met Ko Nyi Pu Lay. After a brief exchange of our family and personal information we hit it off.

His mother, the Burmese communist leader Ba Hein (deceased in November 1946) and my great uncle Zan Yin, Commissioner of Sagaing (now one of the fiercest sites of armed resistance against the coup of 2021), were pupils at the colonial-era National School in Mandalay established and headed by the martyred Muslim educator U Razak. His mother gave me and mother at Zan Yin’s funeral a lift to the cemetery. His sister, the physician, treated Zan Yin as he battled his illness. One cousin of his was my tutor in chemistry at Mandalay University while his youngest cousin and I were classmates since Kinder Garten. My mother, a high school teacher, taught another cousin of his at the old Girls’ Convent known as State High School Number 8.

Looking intently into my eyes “I want to interview and write about you,” said Ko Nyi Pu Lay as we sat down to have street food in Phnom Penh. He continued, “the public perception of you as anti-Aung San Suu Kyi and pro-military) inside the country is not good”. Ko Nay Win, the secretary of Mandalay YMCA listened on at a little short table while waiting for drinks and snacks. In response, I declined, and said to him, “I think it better to keep your trip and participation in my anti-genocide program under wrap (from the military intelligence) than clearing up my name.”

I was profoundly grateful – that one of the country’s loved dissidents and acclaimed writers would use the power of his pen to confront the public (mis)perception. The thought counted, and it counted a great deal, coming from someone whom I held in high regards since my teenage years.

He immediately got the point.

Subsequently, he would travel thousands of mile to join various events I had organized as part of the international anti-genocide and pro-democracy support campaigns. He would lend his name and association to help my activism. I found him video-recording and photographing events and individuals, which he would without fail share with me, for public use.

Nyi Pu Lay poses for the photograph in Mandalay, Myanmar on 18 June 2013. Wikipedia Commons

We spent days and nights together, learning, talking, debating, singing, teaching one another in Bangkok, Phnom Penh, Siem Reap, Kuala Lumpur, and Oslo. On a chartered bus. On a boat. Walking in the compounds of temples and pagodas. We sat on the sidewalks or people’s squares. Toured tortured chambers and killing fields of Cambodia. We sipped beer and whisky. We attended LIVE proceedings at the Khmer Rouge Tribunal. We talked with Khmer genocide survivors and listened to expert talks and briefings by different legal teams and genocide experts. We cracked political incorrect jokes. When travel was difficult, we would hold discussions on Zoom.

After the coup of 2021 during which he went into hiding, he graciously accepted by outreach to be a part of the Zoom-based Burmese community of thinkers, activists, artists and writers who wished to learn and disseminate ideas about “decolonizing” knowledge. But the escalating violence and brutal repression by the perennial enemy of the people – Myanmar’s armed forces – have forced us to reprioritize activism – from focusing on the power of ideas to providing real assistance to Generation Z and others literally fighting back the genocidal regime.

Nyi Pu Lay, the man, treated anyone who met him with basic respect. He was courteous, thoughtful, kind and generous – with his time, talents and publications. Above all, he was modest and brimming with curiosity and eagerness to learn not just about things that immediately concerned the Burmese mind, but racism, international law, democratization, transitional justice, genocide and other atrocity crimes.

On my part, I know that my generation of anti-dictatorship dissidents – and I certainly do – stand on the shoulders of the previous generation, including that of Ludu Daw Ahma and U Hla, my parents and the brothers of Nyi Pu Lay, and Nyi Pu Lay’s own generation. Despite their failures to bring down the military dictatorship, their lives remain the single most important source of inspiration. Both their contributions lives need to be memorialized and celebrated, irrespective of the outcome of their labour.

Knowing the long and honourable history of Nyi Pu Lay family’s resistance to state repression and class exploitation, I see the passing of my fellow dissident – and a fellow Mandalayan at that!, not simply as a loss to our sustained resistance movements – now in its 7th decade. But it was something more profound that that. It signifies a death of an era or a particular type of politics, anchored in a deep sense of uncompromised principles, genuine camaraderie, mutual appreciation and fundamental respect. He was the last, or one of the last dissidents, in a long line of highly principled dissidents who would oppose any form of repression, subjugation and exploitation, racial, religious or class.

Nyi Pu Lay was more than a dissident. He was a rich depository of historical knowledge, or local knowledge. He knew so many important personalities in revolutionary circles, both literary and political. He was in the thick of events and processes. He was a witness to Myanmar’s political and cultural history. I can only hope that he had recorded in some form or others his vast knowledge

Some of us privileged to have known and worked with him will, I know, continue to uphold the principles of justice, equality and freedom which had guided your remarkable family of revolutionaries for nearly a century.

Rest in the Revolution, Brother.

Maung Zarni

A FORSEA PHOTO-ESSAY IN MEMORY OF NYI PU LAY

Nyi Pu Lay (in black t-shirt, holding the camera) listening to the Cambodian tour guide at the Interrogation Centre known as S-21, Phnom Penh, 2014.

Nyi Pu Lay is far right. second row from the front, anti-genocide Myanmar activists, attending a legal presentation at the Khmer Rouge Tribunal also known as Extraordinary Chambers of the Court of Cambodia or ECCC , 20 Oct. 2014.

Nyi Pu Lay (second from Far Right) with a team of anti-genocide activists from Myanmar, Cheung Ek K Cambodia Genocide Museum (or Killing Field), Oct. 2014.

From left to right: Ko Nyi Pu Lay, Zarni, Nay Ko Nay Win and Sithu Aung Myint, Ankor City, Siem Reap, Cambodia, 2014.

Ko Nyi Pu Lay (far left, front row) with Myanmar writers, activists and artists, National Museum of Cambodia, Phnom Penh, 2014.

KO Nyi Pu Lay, (in white T-shirt, holding the camera, with Myanmar attendees at the Oslo Conference on the Rohingya Genocide), Oslo Airport, May 2015.

From Right to Left: Nyi Pu Lay, the dissident singer Mun Awng, Mandalay YMCA Secretary Ko Nay Win and Myanmar Methodist Bishop, Norwegian Nobel Institute, Oslo, May 2015

Below: Myanmar dissident artist Mun Awng’s solidarity performance at the Oslo Conference on Rohingya Genocide, The Norwegian Nobel Institute, Oslo, 26 May 2015. Video recording by courtesy of the late Nyi Pu Lay (1952-2023).